Level Five “Strategist” Leadership for Complex Adaptive Groups

This blog is a companion to the interview with Terri O’Fallon. What is A Level 5 / Teal Organization? Terri O’Fallon, PhD, wrote this post.

This blog is a companion to the interview with Terri O’Fallon. What is A Level 5 / Teal Organization? Terri O’Fallon, PhD, wrote this post.

The world is a complex place. We are connected and interconnected in ways from which we can no longer retreat with the Internet, and the contemporary ways make us visible to every pair of eyes that look our way. So, how do we lead in this interconnected atmosphere that is changing so quickly? When we are continually connected to the internet, how can we know that any fact in the sea of information we swim in daily is true?

In today’s climate, much truth can come from within you, the leader, by knowing how to engage with the complex, adaptable contexts we live in daily.

Four strategies support building working environments and systems that can improve a leader’s effectiveness and efficiency as a leader in a complex adaptive team or organization. These four strategies come out of the research from the STAGES developmental model, which was derived by integrating developmental approaches related to 1. our individual beliefs and values, 2. our individual action orientation, 3. the norms and culture of the team or organization and 4. the structural and systemic elements. Using these strategies will not only help leaders achieve their goals but will make work a pleasure.

- Support the developmental growth of the people in your organization.

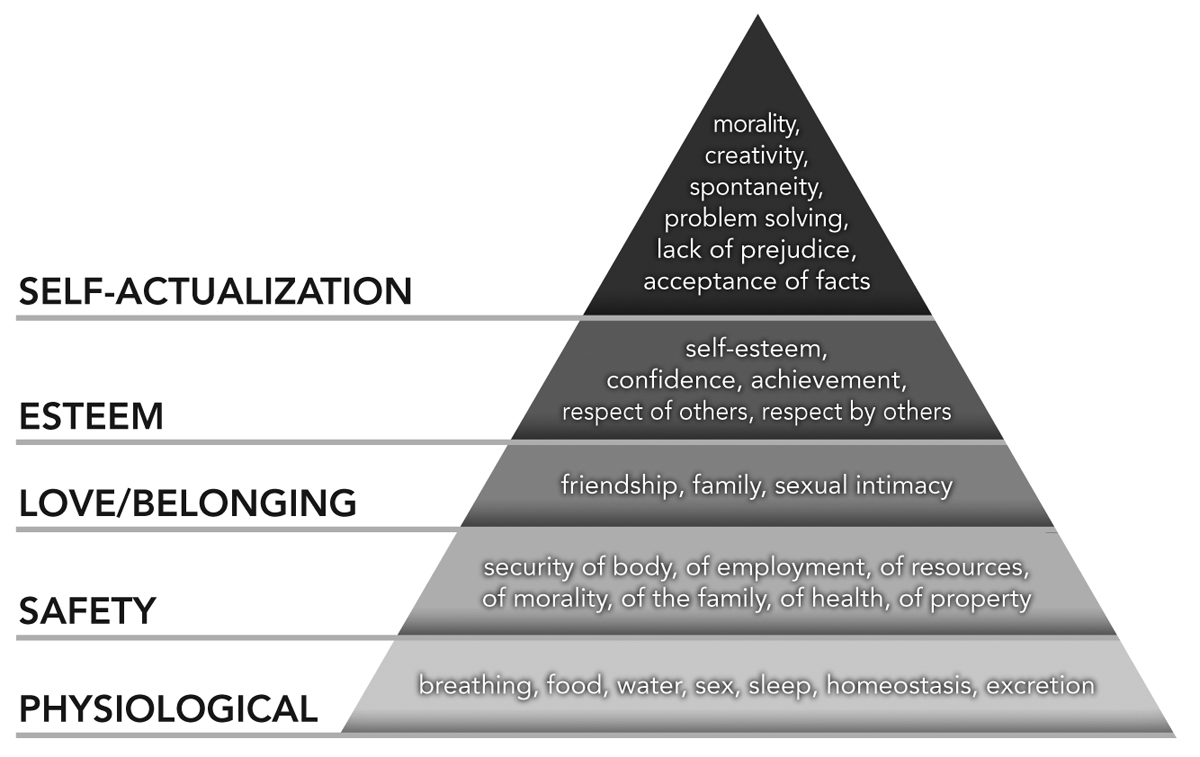

We grow and develop all our lives. However, growth isn’t like climbing stairs to the top. Developmental maturity is more like blowing up a balloon. As a result, one grows and matures in wisdom, intelligence, compassion, relationships, and skills, one breath at a time. Becoming familiar with these well-documented stages of growth is an important window into the worldviews and beliefs of individuals and how those views shape your organization. Promoting developmental change and understanding how transformation occurs can shatter a hidden glass ceiling that could stunt the growth of people in your organization who are constrained by current organizational limitations.

- Embed goals in ethical principles that you will not sidestep.

Goals are useful targets, but they do not inherently have virtuous results. Part of success is adapting to any goal or target as new landscapes come into view. Adapting goals quickly to changing conditions can inhibit unintentional negative side effects to keep them alive and operable without adapting. Developing a set of principles that guide your adaptations can keep your revisions within ethical boundaries and enhance the results you want to achieve in the world. For example, if your principle is transparency, you would know immediately if you were hesitant to be forthright about an alteration of a process in action, and upon examination, you might discover unconscious underlying reasons for your hesitation in being transparent. Whatever the principles are, they can mold and shape goals and dictate how they are reached as they adapt to changing contexts. By deciding up front a set of principles you will not go outside of, you can quickly make decisions about any variations in your aims and be less apt to cause unintentional harm to others, society, and the bottom line.

- Experiment with small changes and then try them on yourself.

A strategist (level five) leader can stand back and see the systems s/he is working with and the organizational environment. This kind of leader can evaluate the weak links in the system and strengthen those places, often in collaboration with others. If the adaptation works, you will see positive change in those who work in the organization, and one way you can know that your change is appropriate is if it grows you and others. You can experience this by stepping back into the system you have adapted and noticing how you experience the change as it applies to you personally and, through that lens, how it applies to others.

- Work with individual and collective shadow issues.

This is one of the most challenging parts of being a strategist (level five) leader, as tested by STAGES. At strategist (level five), people are willing to take personal risks in updating their perceptions and behaviors and in addressing organizational inconsistencies. The obvious one at this level is seeing your projections (getting frustrated by others who have qualities you don’t recognize or acknowledge in yourself). You will know if you are projecting if you catch yourself judging someone or assuming something about someone, and after you reflect at the end of the day on these judgments and assumptions, you may begin to see patterns of behavior in yourself that bother you in others. It helps to write them down and provides a tool to evaluate what you judge in others and yourself.

The truth is that we can’t judge what is in others unless we also have that experience somewhere inside ourselves. For example, when driving and someone cuts you off, you may find yourself extremely angry. If you can see your projection, you might ask yourself, “Have I ever cut someone off in traffic?” Projecting our judgments is common, and we are usually unaware that we also own the same qualities we find annoying in others.

Identifying projections is very important because, in organizations, we may find fault with others for things we are doing. By identifying the projection, we can address our disruptive behavior and change our relationship with others. After we have addressed our behavior, we can invite others to do the same.

This approach helps you as a leader find both the challenging and positive capacities in yourself that you don’t see and helps you see how much you are like others you judge or criticize. This understanding alone can help resolve tense situations that inevitably arise.

These projections permeate most groups or organizations (collectives) . There will frequently be times when there are self-righteous and indignant accusations among people working together, between departments, and between organizations. Over time, unconscious collective agreements become organizational habits that can inhibit creativity and honesty and lead to ineffectiveness. Collective examination and identification of these unconscious and often limiting habits can improve effectiveness and benefit the whole organization and, potentially, innovation.

These projections are like putting a rubber band around a tree and then around your waist. You can stretch that rubber band only so far, and it will eventually halt or slow progress—or worse, snap and throw you back.

We use the STAGES matrix to identify these hidden areas, to find the specific areas that need attention, and to create interventions that are effectively and efficiently targeted for healthy adaptive change.

To learn more about the StAGES model and Terri’s work, visit Terri’s website, “Developmental Life Design”

About the Author

Terri O’Fallon, PhD has focused the last 23 years as an applied researcher, Terri O’Fallon’s focus over two decades has been on “Learning and change in Human Systems”. She has worked with hundreds of leaders studying interventions that most result in developing leaders who can effectively implement change. She has a PhD in Integral Studies from the California Institute of Integral Studies.

Terri is also the co-founder of two organizations. She and Kim Barta have created Developmental Life Design, an organization that focuses on how the STAGES (developmental) model can support insight into our growth as people, leaders, guides, and coaches and the impact these insights have on our influence in human collectives.

She also partners with Geoff Fitch and Pacific Integral, using the STAGES model to develop collective insight and developmental growth experiments.