The Ecosystem Decision-Making Radar

Christoph Hinske, associate professor at SAXION University of Applied Sciences, with contributions from Tom Grote, Chief Catalyst at Edge Innovation Hub, shared their insights in the podcast Applying Innovative Leadership Concepts. The following article illustrates the concepts discussed.

| Link to the entire interview: |

Making high-quality decisions in complex situations requires more than just knowing the conducive or inhibitive factors defining the probabilities of our success. Instead, riding the complexity wave asks us to understand how these factors interrelate, form dynamics and how our fundamental emotions and belief systems influence our decisions.

Taking on this responsibility is challenging since few tools exist that combine strategic decision-making in complex situations with emotional intelligence, business ecosystem thinking, and system dynamics.

The Ecosystem Decision-Making Radar (the Radar) is about to change just that. It intends to help you and your organization build your emotional intelligence by mapping out the consequences (both good and bad) of how you choose to respond in complex situations. To map out and learn from our decisions strategically, we must know our individual and organizational values, superpower, and core identity. Unfortunately, many do not take this step as they lack the tools to correlate it to their performance. Yet, we believe this step to be essential, and without it, we are just fumbling in the dark.

Consequently, my colleagues and I tried to build a robust leadership tool that combines emotional intelligence with systems thinking, system dynamics, and strategy. It intends to increase the performance of you, your organization, and your stakeholder relationships alike.

An observation I did when activating entrepreneurial ecosystems

In 100% of my projects on activating entrepreneurial ecosystems, leadership struggles to see the consequences of individuals’ emotionally impaired responses individuals on their own, their organizations’, and stakeholders’ success.

- This phenomenon leads to an average of €140,000 extra costs, considering that the medium time spent solving the resulting frictions, redundancies, silo structures, and stress is about 40% per process step, essentially squeezing business models to death.

- Each actor in the Entrepreneurial ecosystem loses roundabout 40% of potential new revenues due to the vanishing of possibilities, thus, increasing the probability of becoming obsolete.

- These well-intended economic development measures lose approximately 60% of the highly engaged and loyal leaders, resulting in up to 100% of brand value destruction for the project owners.

A decision I made, to stop contributing to the destruction of value I do not own

Being a passionate action researcher and “pracademic”, I decided not to accept these devastating outcomes anymore. Mainly, I stopped taking three fundamental beliefs for granted, helping me to develop the Ecosystem Decision-Making Radar:

- Wrong assumption #1: People can choose to be emotional or not, and emotions are threatening success in professional meetings; aka “He should stop being so emotional, he kills our performance!”

- Wrong assumption #2: The relation between primary emotional states and resource performance in complex entrepreneurial ecosystems is hard to map and measure.

- Wrong assumption #3: Decision-makers refuse to consider the behavioral impacts of unreflected emotional states on their processes and outcomes.

Helping leaders overcome these assumptions is even more critical as advances and access to technology imply that our context moves ever faster. Consequently, the opportunity costs of not using a systemic approach to decision-making are growing exponentially.

A tool I developed to support leaders to navigate their complexity

I started to study the effect of our primary emotional states and how these affect our behaviors and decisions. During several months of trial and error, I related my observations to insights offered in such articles as those referenced at the end of the post.

A tool started to emerge. I called it “The Ecosystem Decision-Making Radar” or just The Radar. This tool begins from a few basic assumptions:

- Humans are always in one of eight primary emotional states if we want or not.

- For a short moment, we are victims of this emotion, and that is fine!

- Our ability to identify our states and define their impact on our behaviors is a conscious choice.

- Naming, mapping, and reflecting our behaviors help us grow as leaders and positively contribute to our organizations’ and entrepreneurial ecosystem’s success.

One day during a coaching session, my client, a director of one of the largest, oldest, and most well-known nature conservation groups in Germany, helped me see the game changer!

We were mapping his behavioral response to an emotional state during a video conference with a minister of state. He suddenly stopped talking, looked at me in amazement, and held his coffee mug in front of the camera. On the cup, it stated: “There is a space between stimulus and reaction. In this space lies our power to choose our response. Our development and our freedom lie in our reactions.” — Viktor Emil Frankl.

Now, it is essential to know that Viktor Frankl was an Austrian neurologist, psychiatrist, philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor; * March 26, 1905; † September 2, 1997.

My coachee explained to me that the Radar helps him live the phrase. It empowers him to take responsibility for his intrinsic intentions (aka SuperPower or Core Identity) by acting out his core values. In later sessions with him and others, I figured out that the Radar creates awareness of the primary emotional states, enabling leaders to produce intended results by performing appropriate behaviors/actions rooted in their fundamental values. This transparency and heightened awareness of the impact their “inner systems” have on the world around them helps them act much more consciously in their stakeholder relationships, allowing them to co-create value with much more efficiency. We started to observe that he drastically reduced most of the costs stated at the beginning of the article just after a few sessions.

How the tool can help you become a better leader in complex entrepreneurial ecosystems

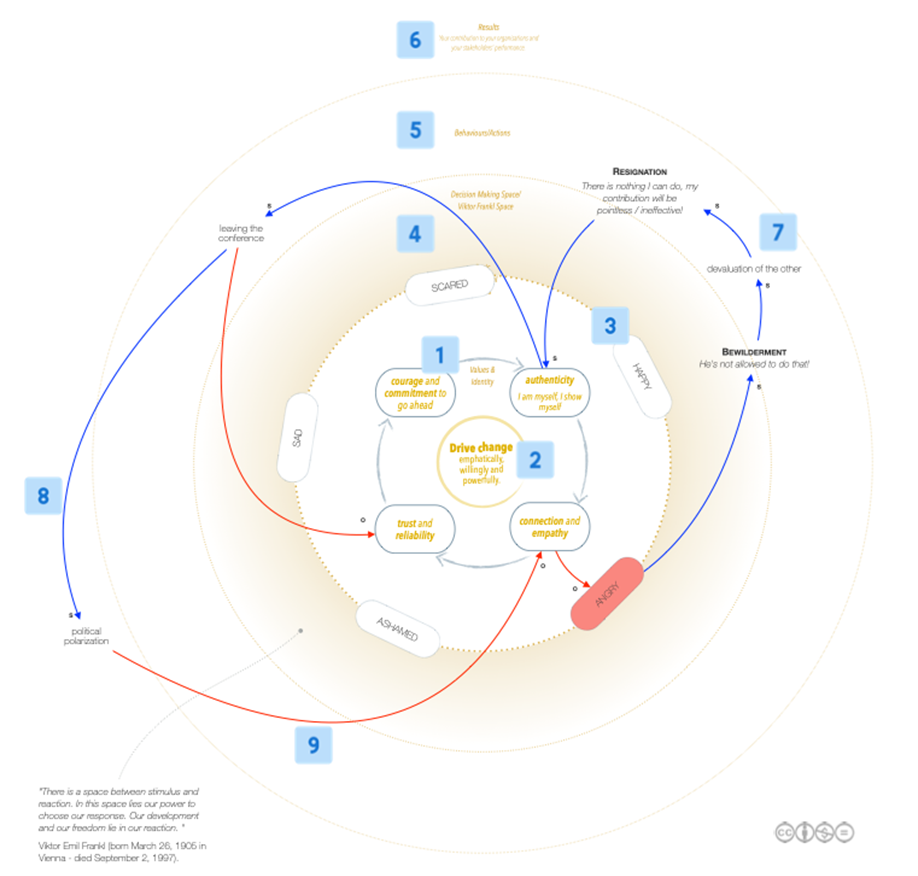

In the situation mapped out in the image below, the process helped my coachee identify patterns of behavior that benefit his and his organizations and stakeholders’ success.

Figure 1: The causal relationships between the elements in this Mental Model use the approach of Causal Loop Diagramming. For further information on more identified patterns and how to read and develop such simple yet powerful system models, please get in touch with c.hinske@saxion.nl

A simple rundown of how to read and build a model

- Core Values Flywheel: If activated, it nourishes our SuperPower and Core Identity, causing positive emotions. If hampered from turning, it causes negative emotions.

- Core Identity and Superpower: It is the emerging pattern happening when our core values flywheel is turning.

- Primary emotional states: There are 4 to 8 primary emotions. We map secondary emotions in the outer circles of the model. Primary emotions form a filter shaping our behaviors.

- Decision-Making Space: It is the moment shortly after an emotional response but before our behavioral response. In this instant, we have the power to choose. Before, it’s too early as our primary emotion directs us. Afterward, it’s too late since our behaviors already shaped the situation. See also the quote by Viktor Frankl.

- Behaviors/Activities: We execute conscious or unconscious behaviors and actions in a given situation after experiencing a primary emotion.

- Results: The contribution we make to our organizations and our stakeholder’s performance in a given situation. The quality of the results defines resource performance and opportunity costs.

- Factors: Aspects that happen or that one does, together with their causal relationships (arrows), form a system.

- Blue arrows: the more of A, the more of B, or the less of A, the less of B (S = same directional development)

- Red arrows: the more of A, the less of B, or the less of A, the more of B (O = opposite directional development)

In the case of my coachee, it showed him that responding to his primary emotion of anger with devaluating his opponent, leaving the video conference; he fled into a wrong belief of being authentic. He started to understand that a behavioral response, which he was initially proud of, undermined his long-term success of being a trusted, reliable leader since he increased political polarization.

Our next step aims to identify more systemic patterns and archetypal behaviors to develop hands-on tools for leaders acting in complex stakeholder systems. We want to understand how unreflected emotional states threaten the activation and stable functioning of entrepreneurial ecosystems mentioned at the beginning of my blog post. Solving this leadership challenge will make a major contribution in solving current and future transformation processes (e.g. energy systems, circular economy, digitalization).

My coachee’s outcomes and next steps

He is starting to use the Radar with all his teams, integrating the models to understand his organizations’ SuperPower, core values, opportunity spaces, and efficiency gains. His next step is to do the same for the stakeholder landscape of his organization, allowing him to identify growth and lobby strategies that serve them and the greater good at the same time.

He learned:

- He cannot choose to be emotional or not and that this is perfectly fine.

- Emotions only threaten his success as a system leader if he does not name them. Naming them increases the odds to respond appropriately, taking over responsibility for the outcomes he creates.

- He now actively manages the relationship between his primary emotional states and the resource performance in his complex actor ecosystem.

Further reading:

- Anuwa-Amarh, E., & Hinske, C. (2020, June 1). Thought Leaders – Compelling new writing about the Sustainable Development Goals by leading experts. Retrieved from https://www.taylorfrancis.com/sdgo/about/leading-thoughts?context=sdgo.

- Beehner, C. G. (2019). System Leadership for Sustainability. Routledge.

- Duhigg, C. (2014). The Power of Habit – Why we do what we do in life and business.

- Fredin, S., & Lidén, A. (2020). Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: towards a systemic approach to entrepreneurship?. Danish Journal of Geography, 120(2), 87–97. Routledge | Taylor&Francis

- Hawkins, P., & Turner, E. (2019). Systemic Coaching. Routledge.

- Hüther, G. (2006). The Compassionate Brain – How empathy creates intelligence. Shambhala Publications.

- Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2009). Immunity to Change – How to Overcome it and Unlock the Potential in Yourself and Your Organization. Harvard Business Press.

- Wheatley, M. J. (2017). Who Do We Choose To Be? – Facing Reality, Claiming Leadership, Restoring Sanity. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

About the Author and the Contributor

Christoph Hinske is an associate professor at the School of Finance and Accounting at SAXION University of Applied Sciences, covering Systems Leadership and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. In his work, Christoph observed that our rapidly transforming economies force leaders to be systemic since they need to act in complex, ambiguous ecosystems. Consequently, his research focuses on empowering leaders to change their strategic and operational models from linear to circular to ecosystemic. He observed that 80% of organizations, intending to transform their models to be more systemic, continue doing the old stuff, using new fancy words. They still apply the same tools, mindsets, and frameworks developed to build linear success.

Thomas Grote is chief catalyst for the Edge Innovation Hub, an ecosystem dedicated to building principle-based businesses that lead with love and drive food innovation to the edge of possibility. Thomas grew up working with his parents and siblings at the first Donatos Pizza. As chief operating officer, he helped grow the family business from one restaurant to a regional chain which the family eventually sold and then later repurchased from McDonalds. He opened Central Ohio’s first visible and welcoming LGBTQ+ themed restaurant and helped found a non-profit, Equality Ohio, to advocate for equity and inclusion in his home state. Thomas also served as chief financial officer for a UK-based biotech company focused on commercializing plant-based chemicals. Thomas graduated with a finance degree from Miami University and earned his MBA from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. He resides in Columbus, Ohio with his husband and two daughters.

Photo by Jens Lelie on Unsplash